Mismanaged Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR) can cause Birth Injuries such as HIE & Cerebral Palsy

Fetal growth restriction (FGR), also called intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), is a term used to describe an unborn baby with an estimated weight that is less than the 10th percentile for gestational age. In other words, the baby is smaller than expected because it is not growing at a normal rate in the womb. FGR has many causes, but the condition is most often caused by an insufficient nutrient supply. It is very important for physicians to recognize conditions that can cause FGR/IUGR. In addition, assessing a baby’s growth is an important part of prenatal care; physicians must be aware of any growth problems in the baby.

Babies that have fetal (intrauterine) growth restriction are at risk of experiencing conditions such as the following:

Causes of Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR) / Intrauterine Growth Restriction

There are many causes of fetal growth restriction, but they all usually cause FGR / IUGR by the same mechanism: decreased nutrition as well as reduced blood flow in the network of vessels in the uterus and placenta (utero-placental circulation) and poor fetal nutrition.

The utero-placental circulation is crucial in getting oxygen-rich blood and nutrition to the baby. In addition, this circulation is how the baby gets rid of waste such as carbon dioxide. Oxygen-rich blood and nutrients are transported to the baby through vessels that run through the uterus and placenta and then to the baby through the umbilical cord. Conditions that affect the utero-placental circulation or umbilical cord can cause the baby to receive inadequate oxygen and nutrition. FGR / IUGR can be caused by:

Causes of Fetal (Intrauterine) Growth Restriction

- Partial placental abruption

- Umbilical cord abnormalities

- An abnormally small placenta

- Multiple gestation (twins, triplets or more)

- Maternal diabetes prior to pregnancy

- Gestational diabetes

- Oligohydramnios (low amniotic fluid)

- Maternal kidney problems

- Any long-term condition that causes blood vessel problems in the mother, such as long-term high blood pressure and high blood pressure caused by pregnancy or preeclampsia

- Poor weight gain during pregnancy

- Mother weighs less than 100 pounds prior to pregnancy

- Poor weight gain during pregnancy

- Maternal heart or lung disease

- Smoking, drinking alcohol or drug abuse

- Sickle cell anemia

- Maternal anemia or malnutrition

- Infections in the mother, such as rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, and syphilis

- Exposure to medications called teratogens, which include valproic acid, warfarin and cyclophosphamide

- Autoimmune diseases in the mother, such as systemic lupus erythematosus

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome in the mother

- Genetic and structural disorders of the fetus, such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18, congenital heart disease and gastroschisis

Diagnosing Fetal Growth Restriction

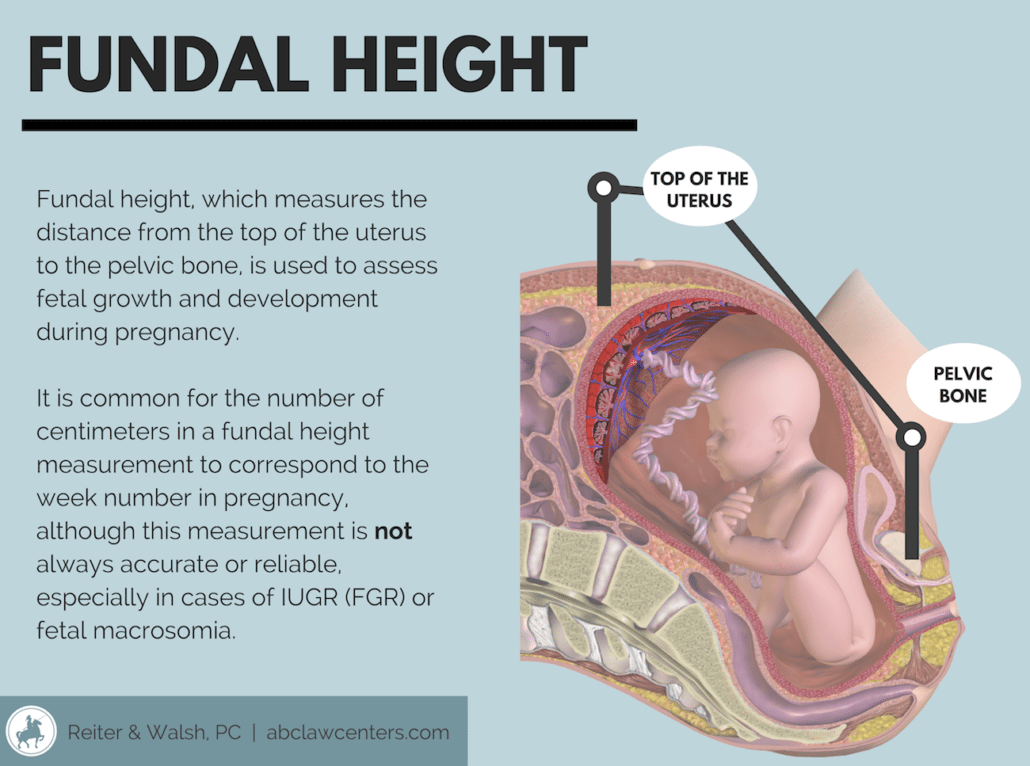

Fetal growth restriction is sometimes suspected by a physician during a routine prenatal exam when the fundal height (distance from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus) measures the baby as being too small for gestational age. While it is standard practice to start measuring fundal height beginning around 20 weeks of gestation, these measurements can be very inaccurate; they are only accurate in diagnosing FGR about 30% of the time. Thus, the standard of care requires serial ultrasound measurements where there are risk factors for FGR. Risk factors include the conditions listed above as well as a prior history of the mother previously giving birth to a small for gestational age baby, a prior ultrasound that showed the baby having suboptimal growth, and/or a significant lag of the fundal height on physical exam.

Tests Performed to Confirm FGR

Ultrasound. The main test for checking a baby’s growth in the womb is an ultrasound, which involves using sound waves to create pictures of the baby. Ultrasound can be used to measure the baby’s head and abdomen. The doctor can compare those measurements to growth charts to estimate the baby’s weight. An ultrasound is accurate in diagnosing FGR about 80 – 90% of the time. The test can also be used to determine how much amniotic fluid is in the womb. A low amount of amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios) could indicate FGR.

Doppler flow. Doppler flow uses sound waves to measure the amount and speed of blood flow through the blood vessels. This test is sometimes used to check the flow of blood in the umbilical cord and vessels of the uteroplacental circulation.

Weight checks. The mother’s weight is checked at every prenatal visit. If a mother is not gaining weight, it could indicate a growth problem in the baby.

Amniocentesis. This is a procedure where a needle is inserted through the mother’s abdomen and into her uterus to withdraw a small amount of amniotic fluid for testing. Tests may detect infection or some chromosomal abnormalities that could lead to FGR.

Fetal monitoring. The physician will initiate a regular schedule of prenatal tests up through the time of delivery. These tests typically include weekly nonstress tests, biophysical profiles and serial ultrasounds to assess the baby’s heart rate in response to her movement, level of amniotic fluid and to determine the level of fetal growth.

Treating Fetal Growth Restriction

When FGR is diagnosed, the mother should be referred to maternal-fetal specialists. These are physicians with specialized training and expertise in the management of high risk pregnancies.

In addition to determining the likely cause of the FGR, the physician will also initiate a regular prenatal testing schedule. Because of the significant risks associated with moderate to severe FGR, many physicians will deliver their patients prior to term via C-section delivery.

Treatment of FGR based on gestational age includes the following:

- If gestational age is less than 34 weeks, the physician will usually continue closely monitoring the pregnancy until 34 weeks or more. Fetal well-being and the amount of amniotic fluid will be closely monitored. If either of these becomes a concern, immediate delivery may need to take place. When delivery is suggested prior to 34 weeks, the physician should perform an amniocentesis to help evaluate the maturity of the baby’s lungs.

- If the baby’s gestational age is 34 weeks or greater, the physician may recommend labor induction for early delivery.

- If the baby has FGR but the pregnancy is otherwise uncomplicated, delivery is recommended at weeks 38 – 39.

- If the baby has FGR and other pregnancy complications are present (oligohydramnios, abnormal Doppler studies, maternal risk factors such as preeclampsia), delivery should occur at weeks 34 – 37.

- When the mother is pregnant with twins and there is isolated FGR, for dichorionic-diamniotic twins, delivery should take place at weeks 36 – 37. For monochorionic-diamniotic twins, delivery should be scheduled for 32 – 34 weeks. When any twin pregnancy affected by FGR is also affected by an additional complication (oligohydramnios, abnormal Doppler studies, maternal risk factors), delivery should occur at weeks 32 – 34.

- Of course, if there is persistent abnormal fetal testing suggesting that the baby is in imminent danger, delivery must occur immediately, regardless of gestational age.

- One course of steroids should be given between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation the week before delivery is expected.

- When delivery is expected to occur before 32 weeks of gestation, magnesium sulfate should be given prior to delivery for neuroprotection.

Risks to a Baby with Fetal Growth Restriction

Since there is a lack of oxygen and nutrients in babies affected by FGR, there is a decrease in the babies’ stores of glycogen and lipids, and this often leads to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) at birth.

Babies experiencing FGR may have had abnormally low oxygen levels for a long time. A baby responds to this by producing extra red blood cells in a condition called polycythemia. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) may also occur if oxygen levels are diminished for an extended period of time.

Other risks to the baby include the following:

- Meconium aspiration

- Hyperviscosity (decreased blood flow due to an increased number of red blood cells)

- Hypothermia (inability to maintain normal body temperature due to reduced fat on the body)

- Thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count caused from placental insufficiency related to FGR)

- Leukopenia (an abnormal decrease in the number of white blood cells, often reducing immune system function)

- Hypocalcemia (abnormally low blood calcium level)

- Pulmonary hemorrhage (sudden bleeding from the lung)

- Motor and neurological disabilities, brain damage

- Cerebral palsy

- Long-term heart problems

Depending on the cause of FGR, a baby may be small all over or look malnourished upon delivery. The baby may be thin and pale and have loose, dry skin. The umbilical cord is often thin and dull instead of thick and shiny.

In addition to being small, babies affected by FGR often exist in a state of mild to moderate long-term oxygen deprivation and do not tolerate labor well. They are susceptible to fetal distress and heart rate abnormalities. Once an abnormal or nonreassuring heart tracing occurs, it means oxygen deprivation is having a significant impact on the baby and delivery must occur right away (usually by emergency C-section). Given the risk of fetal distress and abnormal heart tracings when a growth restricted baby is exposed to labor, the medical team must closely watch the fetal heart tracings during labor and have everything in place to perform a quick C-section delivery at the first signs of distress.

Failure to properly manage conditions that can cause FGR, such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, umbilical cord problems, placental abruption and oligohydramnios, can cause the baby to have serious complications caused by a lack of oxygen and nutrients. Early delivery of the baby by C-section often must occur when the baby has FGR. Failure to do this can also cause severe injury in the baby. Improper management of FGR can cause hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), permanent brain damage, cerebral palsy, seizures, intellectual disabilities and developmental delays.

Trusted Legal Help for Fetal Growth Restriction

If your child was diagnosed with a birth injury, such as cerebral palsy, a seizure disorder or hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), the award winning birth injury lawyers at ABC Law Centers: Birth Injury Lawyers can help. We have helped children throughout the country obtain compensation for lifelong treatment, therapy and a secure future, and we give personal attention to each child and family we represent. Our nationally recognized birth injury firm has numerous multi-million dollar verdicts and settlements that attest to our success and no fees are ever paid to our firm until we win your case. Contact ABC Law Centers: Birth Injury Lawyers for a free case evaluation. Our firm’s award-winning hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) lawyers are available 24 / 7 to speak with you.

Featured Videos

Posterior Position

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

Featured Testimonial

What Our

Clients Say…

After the traumatic birth of my son, I was left confused, afraid, and seeking answers. We needed someone we could trust and depend on. ABC Law Centers: Birth Injury Lawyers was just that.

- Michael

Helpful resources

- Baschat AA, Galan HL, Ross MG, Gabbe SG. Intrauterine growth restriction. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:chap 31.

- Carlo WA. Prematurity andintrauterine growth restriction. In: Kliegman RM,Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders;2011:chap 91.

- Figueras F, Gardosi J. Intrauterine growth restriction: newconcepts in antenatal surveillance, diagnosis, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):288-300.