Planned Early Delivery for High-Risk Pregnancies

A high-risk pregnancy is one where the mother has a health condition that increases the risk of complications during pregnancy, birth and delivery. In some cases, it is safer to have a scheduled early delivery to prevent birth injuries and ensure the baby and mother are safe. Mothers may ask their OB/GYN or other medical care providers about early delivery if they are high-risk. Conditions that place mothers in the high-risk category include (but are not limited to) placental abnormalities or dysfunction, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, blood clotting disorders, HIV/AIDS, certain infectious diseases or STIs, and seizure disorders.

When Might Planned Early Delivery Be Better for the Baby?

Sometimes a baby must be delivered prior to term. There can be numerous reasons for this, including:

- The environment in the womb is sub-optimal for the baby’s development

- There are indications of conditions that increase the baby’s risk of experiencing a sudden lack of oxygen to their brain (birth asphyxia)

- The mother has a health condition that makes contractions and active labor dangerous for the mother and baby (like in the case of preeclampsia).

When standards of care for the timing and management of early delivery are followed, a preterm birth can help prevent birth injuries and brain damage in the baby.

The Role of Medical History in Deciding When Early Delivery May Be Better

Your obstetrician must obtain a complete and thorough medical history from you as soon as your pregnancy is confirmed. If your health history (or current medical condition) makes you high-risk, your medical care provider should either (a) refer you to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist (MFM), or they can continue your prenatal care – with more frequent prenatal testing to check on your baby’s health. This is very important because the baby can be at risk for many health complications if high-risk pregnancy is not properly monitored and treated. These complications can include:

The Uterus, Placenta and Umbilical Cord’s Role in Your Developing Baby’s Health

Your baby develops inside the womb (uterus) during pregnancy and is surrounded by amniotic fluid. The placenta, which is attached to the inside of the womb, helps bring oxygen and nutrients to the fetus from the mother. Oxygen and nutrient-rich blood travels through vessels that run between the uterus and placenta. This blood is delivered to the baby through the umbilical cord, which arises from the placenta. Conditions that affect the uterus, placenta, umbilical cord and amniotic fluid can cause birth injuries that result in permanent lifelong conditions.

What Makes a Pregnancy High-Risk? When Should My High-Risk Baby Be Delivered?

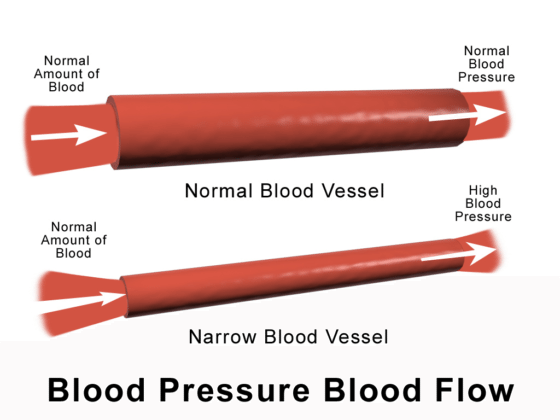

High Blood Pressure and Preeclampsia

High blood pressure (hypertension) during pregnancy can prevent the placenta from getting enough blood, which means the baby will receive less oxygen and nutrients. Preeclampsia is a more severe form of hypertension, and it is diagnosed when the mother has hypertension that is diagnosed after 20 weeks of gestation along with dysfunction in some major organs.

High blood pressure and preeclampsia increase a baby’s risk of:

- Poor fetal growth

- Intrauterine (fetal) growth restriction (IUGR/FGR)

- Placental abruption

- Premature birth

High blood pressure and preeclampsia increase the mother’s risk of:

- Kidney failure

- Hypertensive crisis

- HELLP syndrome

- Eclampsia.

These conditions may be life-threatening to both mother and baby.

High Blood Pressure and Preeclampsia: Delivery at 36-39 Weeks or Sooner

The conditions caused by mismanaged hypertension and preeclampsia can result in the baby having birth injuries such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) and cerebral palsy. Some many women with high blood pressure or preeclampsia, delivery is recommended at 36-39 weeks or sooner, depending on the mother’s health history. Early delivery helps prevent brain damage and other adverse outcomes in the baby.

There are different guidelines for delivery with respect to maternal hypertension:

- Long-term (chronic) maternal hypertension not being treated with medication: Delivery should occur at weeks 38 – 39. If additional complicating issues are present, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Chronic maternal hypertension controlled with medication: Requires delivery at weeks 37 – 39. If there are additional complicating issues, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to occur at an earlier date.

- Chronic maternal hypertension that is difficult to control (requires frequent medication adjustments): Delivery should take place at weeks 36 – 37 If additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Gestational hypertension (hypertension that begins during pregnancy): Delivery should occur at weeks 37 – 38.

- Severe preeclampsia: Delivery should take place as soon as the mother is diagnosed, as long as the pregnancy is at 34 weeks or later. If additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Mild preeclampsia: Baby should be delivered at 37 weeks or later, as soon as the mother is diagnosed. If there are additional complicating issues, such as (IUGR/FGR), delivery may need to occur at an earlier date.

Gestational and Pregestational Diabetes

Approximately 15% of pregnancies are complicated by gestational diabetes, and 3–4% of pregnant women have pregestational diabetes. Diabetes can cause numerous medical problems, including blood vessel problems, excessive glucose being carried to the baby, and a lack of oxygen in the baby’s brain (hypoxia).

Complications associated with gestational diabetes and pregestational diabetes include:

- A large for gestational age (LGA) baby and macrosomia, which increases the baby’s risk of having forceps and vacuum extractors used during delivery, shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injuries, Erb’s palsy and being non-vigorous at birth

- Fetal hypoxia

- Insufficient fetal growth

- Polyhydramnios

- Maternal hypertension

- Preeclampsia

- Reduced uteroplacental perfusion (RUPP)

- Preterm delivery (if mother is obese)

- Neonatal hypoglycemia

- Hyperbilirubinemia (prolonged jaundice)

- Respiratory distress

- Cardiomyopathy (baby has a large heart)

- Hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, polycythemia

In order to prevent the baby from having brain damage, early delivery is indicated in certain circumstances.

Gestational and Pregestational Diabetes: Delivery at 34-39 Weeks or Sooner

There are different recommendations regarding when to deliver a baby whose mother has diabetes. These depend on the severity of diabetes and how well-controlled it is, among other factors:

- Well-controlled pregestational (appearing before the beginning of the pregnancy) diabetes: Late preterm birth or early term birth is not recommended. However, if additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Pregestational diabetes coupled with vascular disease: Require delivery at weeks 37 – 39. If additional complicating issues are present, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be necessary.

- Gestational diabetes that is well-controlled with diet or medication: Late preterm birth or early term birth is not recommended. However, if additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., a delivery prior to term may be indicated.

- Poorly-controlled pregestational diabetes: Requires delivery at 34 – 39 weeks, with specific timing individualized to the mother’s situation. If there are additional complicating issues, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Gestational diabetes that is poorly controlled on medication: Requires delivery at 34 – 39 weeks, with specific timing individualized to the mother’s situation. If there are additional complicating issues, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

Preterm Labor and Premature Rupture of the Membranes (PROM)

Mothers with preterm labor or premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) may deliver spontaneously, but sometimes they do not. Both conditions are associated with choriomnionitis (infection of the amniotic fluid and fetal membranes) and umbilical cord compression, which are very serious conditions with potentially huge impact on the baby. Infections can be passed on to the baby when the mother’s water breaks, causing meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis or encephalitis. Umbilical cord compression can cause HIE, birth asphyxia, and cerebral palsy.

Expectant management is a technique that refers to closely monitoring the mother and baby while delivery occurs ‘naturally’ (ie without induction). Because preterm labor and PROM carry such large risks, expectant management is not recommended for late-preterm labor or early-term PROM.

Preterm Labor and/or PROM: Delivery at 34 Weeks or Older

Experts recommend delivering babies with preterm PROM at or after 34 weeks depending on several factors:

- The mother had a previous spontaneous preterm birth and is currently experiencing preterm PROM: Baby can be delivered if gestational age is 34 weeks or older. If there are additional complicating issues, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- The mother had a previous spontaneous preterm birth and is currently experiencing active preterm labor: Delivery is indicated if there is progressive labor or an additional maternal or fetal indication. If additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

Oligohydramnios

Oligohydramnios is a condition where amniotic fluid levels are abnormally low. Oligohydramnios can be a sign of an underlying health condition that can impact the baby’s development, as it may indicate that the placenta isn’t functioning properly. It is associated with the following complications:

- Lack of oxygen to the baby’s brain

- Abnormal nonstress tests

- Non-reassuring fetal heart rates (especially decelerations)

- Fetal intolerance to labor

- Meconium aspiration

- Low Apgar scores.

Oligohydramnios coupled with intrauterine (fetal) growth restriction is an ominous pregnancy condition.

Oligohydramnios: Delivery at 36-37 Weeks or Sooner

Scheduled delivery in the context of oligohydramnios should take place before the baby is harmed by complications associated with the condition, such as umbilical cord compression or placental dysfunction. Typically, delivery should occur at weeks 36 – 37. If additional complicating factors are present, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to take place earlier.

Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR)/ Fetal Growth Restriction (FGR)

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (or fetal growth restriction (FGR)) describes an unborn baby with an estimated weight less than the 10th percentile for gestational age. This means the baby is smaller than they should be because they are not growing normally.

IUGR has many causes. IUGR is most often caused by insufficient oxygen supply getting to the baby or poor maternal nutrition, which can be caused by placental insufficiency.

It is very important for physicians to recognize conditions that can cause IUGR. In addition, assessing a baby’s growth is an important part of prenatal care; physicians must be aware of any growth problems in the baby.

Babies with intrauterine growth restriction are at risk for:

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)

- Brain damage

- Cerebral palsy

- Seizure disorders

- Intellectual disabilities

- Developmental delays

Prenatal care of a baby with IUGR involves:

- Determining the cause and severity of the growth restriction

- Closely monitoring the baby’s well-being

- Consulting with specialists

- Selecting the appropriate time for and method of delivery

Delivery in the Context of Intrauterine Growth Restriction Depends on Multiple Factors

There are many factors that feed into the decision to deliver an IUGR baby early. IUGR babies are more fragile than babies with normal growth, which means they are more susceptible to brain bleeds and birth complications. Often these babies cannot tolerate the physical force of vaginal delivery and must be delivered via C-section for safety.

The following are guidelines for delivering babies with IUGR:

- Baby has IUGR and no other complicating conditions: Baby should be delivered at 38-39 weeks.

- Baby has IUGR and other complicating conditions (such as oligohydramnios, other maternal risk factors, abnormal Doppler studies or other long-term disease processes): Baby should be delivered at 34-37 weeks.

- There is persistent abnormal fetal testing suggesting imminent fetal jeopardy: Deliver immediately via emergency C-section, regardless of gestational age.

Guidelines for delivery of babies with IUGR are different if there is more than just one baby. IUGR in twins is managed differently because twins are at a higher risk of complications:

- Dichorionic-diamniotic twins with IUGR and no other complicating conditions: Deliver at weeks 36-37.

- Monochorionic-diamniotic twins with IUGR and no other complicating conditions: Deliver at weeks 32-34.

- Monochorionic-diamniotic twins with IUGR and additional complications (like oligohydramnios, abnormal Doppler studies, maternal risk factors, the presence of 2 or more chronic conditions): Deliver at weeks 32-34.

- Twins with any complicating conditions: Deliver at 32-34 weeks. Complication conditions include (but are not limited to) oligohydramnios, maternal risk factors, abnormal Doppler studies, and any long-term disease processes).

- Regardless of gestational age, twins must be delivered via prompt emergency C-section delivery if there is persistent abnormal fetal testing indicating imminent fetal jeopardy.

Twins, Triplets and Multiples

Twins, triplets and multiples are at higher risk of pregnancy and birth complications, especially spontaneous preterm delivery and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Monochorionic twins are at risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), where the babies get uneven blood flood from the placenta. Other potential complications with multiples include:

- Premature rupture of the membranes (PROM)

- Infection, which can cause sepsis, meningitis, brain damage, HIE and cerebral palsy

- Meconium aspiration

- SGA

- Discordant growth

- Birth asphyxia

- Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy.

- Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL)

- Cerebral palsy

- Intellectual disabilities

Babies in a multiples pregnancy may need medical intervention as soon as they are born. This may include:

- Resuscitation

- Cardiovascular support

- Respiratory support

- Blood transfusions

- Surgery.

This means that a pediatric team should be at the delivery so each baby has a team of medical specialists ready to quickly provide care. Blood products and other potential medical treatments should also be ready. Having a team and critical treatments ready is one of the advantages of a scheduled early delivery.

Scheduled deliveries allow medical staff to:

- Provide important in-utero treatments to help prevent birth injuries and brain damage.

- Prevent PROM and the risk of infections being passed to the baby by having a scheduled birth

- Prevent brain damage due to oxygen or nutrient deprivation.

Twins, Triplets and Multiples: Delivery at 38 Weeks or Sooner

There are numerous guidelines regarding when to deliver babies in a multiples pregnancy:

- Dichorionic-diamniotic multiples: Deliver at 38 weeks. If there are additional complicating factors, such as placental abruption, IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to occur earlier.

- Monochorionic-diamniotic multiples: delivery should occur at 34 – 37 weeks. If there are additional complicating factors, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to occur closer to week 34, maybe sooner.

- If the multiples are dichorionic-diamniotic or monochorionic-diamniotic with a single fetal death: If the death occurs at or after week 34, consider delivery. This recommendation is limited to pregnancies at or after week 34; if the fetal death occurs before the 34th week, delivery is individualized based on concurrent maternal or fetal conditions. If there are additional complicating factors, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be indicated.

- Monochorionic-monoamniotic multiples: delivery should occur at weeks 32 – 34. If additional complicating factors are present, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to occur earlier.

- If the multiples are monochorionic-monoamniotic with a single fetal death, delivery should be considered and individualized, with gestational age and other complicating issues taken into consideration. Additional complicating factors, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., may necessitate a prompt delivery.

Other Conditions that May Require Planned Early Delivery

Health during pregnancy is a complex topic, and there are many reasons why it might be recommended that babies be delivered early. Some other conditions that may require early delivery include:

- Placenta previa: When the placenta grows so close to the opening of the uterus it partially or completely blocks the mother’s cervix (or “cervical os”), the opening to the birth canal. This can lead to severe bleeding and hemorrhaging if mismanaged. Delivery should take place when the baby’s gestational age is 36 – 37 weeks. If there are additional complicating factors, such as intrauterine (fetal)growth restriction (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to occur earlier.

- Suspected placenta accreta, increta, or percreta with placenta previa. Placenta accreta, increta and percreta are abnormalities of placental implantation. When these conditions are present, the baby should be delivered at 34 – 35 weeks, and if additional complicating factors are present, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., the baby may need to be delivered closer to week 34, maybe sooner.

- The mother had a prior classic C-section, with an upper segment

uterine incision. In this case, the baby should be delivered at 36 – 37 weeks. If there are other complicating issues, such as IUGR/FGR, preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be required. - Prior myomectomy necessitating C-section delivery. A myomectomy is surgery to remove pelvic tumors. Myomectomy is associated with an increased risk of uterine rupture during a subsequent pregnancy. As such, most experts recommend a C-section delivery. Delivery should occur at weeks 37 – 38. Earlier delivery may be required in situations where the mother had a more complicated or extensive myomectomy. Also, if the mother has other pregnancy complications, such as IUGR/FGR or preeclampsia, etc., delivery may need to take place even earlier.

- Prior unexplained stillbirth. Late preterm birth or early term birth is not recommended for this situation. Amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity should be considered if delivery is planned at less than 39 weeks. If additional complicating issues exist, such as (IUGR/FGR), preeclampsia, etc., an earlier delivery may be

Indicated. - Fetal congenital malformations: A baby who has any of the following conditions should be delivered at 34 – 39 weeks:

- Suspected worsening fetal organ damage

- Potential for brain bleeds/intracranial hemorrhages (e.g., vein of Galen aneurysm, neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia)

- Delivery that should occur prior to the onset of labor (e.g., EXIT procedure)

- A previous fetal intervention

- Concurrent maternal disease (e.g., preeclampsia, chronic hypertension)

- The potential for adverse maternal effect from the fetal condition

- However, immediate delivery is required regardless of gestational age if 1.) intervention is expected to be beneficial, 2.) fetal complications develop (abnormal fetal testing, new-onset hydrops fetalis, progressive or new-onset organ injury, or 3.) Maternal complications develop (mirror syndrome).

Planned Early Delivery Allows Medical Staff to Provide Life-Saving Medication

When preterm birth is about to occur, obstetricians must make every effort to prevent complications associated with preterm birth, including:

- Respiratory distress

- Sepsis

- Brain bleeds

- PVL

Preventing Preterm Birth Complications with Betamethasone

When a baby is at or less than 34 weeks of gestation and the obstetrician is planning a preterm delivery, the baby should be given a steroid such as betamethasone. Betamethasone reduces the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), intraventricular hemorrhages (brain bleeds), sepsis and PVL. Steroids such as betamethasone help the baby’s lungs and tissues mature.

Preventing Preterm Birth Complications with Magnesium Sulfate

Magnesium sulfate should also be given in-utero when preterm birth is about to occur. Premature babies are at an increased risk for brain injury and cerebral palsy. Magnesium sulfate protects the baby’s brain and reduces the risk of the baby having major motor impairments.

Magnesium sulfate helps protect the baby’s brain by:

- Increasing blood flow in the baby’s brain

- Reducing the damaging molecules that are released when a brain injury (like birth asphyxia) causes brain inflammation

- Providing antioxidant effects

- Reducing neuronal excitability (a process that damages the brain during an insult)

- Stabilizing membranes in the brain

- Preventing large blood pressure fluctuations

Magnesium sulfate should be given approximately 24 hours before preterm delivery and it is administered when the baby is between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation. It can be given to women with preterm PROM, preterm labor with intact membranes and indicated preterm delivery.

Planned Early Delivery Allows Medical Staff to Avoid Birth Injury

Early, scheduled delivery can be crucial in preventing birth injuries such as HIE, brain damage and cerebral palsy. Early delivery allows the baby to be delivered before an underlying condition worsens or causes secondary complications. Planned deliveries enable medical staff to provide in-utero drugs to help protect the baby’s brain. They also allow preparation time to make sure that important medical treatments (like blood transfusions) are readily available. Planning is crucial in ensuring the presence of enough staff and medical equipment to properly care for the mother and baby.

Trusted Birth Injury Attorneys Helping Children Since 1997

The birth injury attorneys at ABC Law Centers: Birth Injury Lawyers focus exclusively on birth injury. Our firm helps families and children impacted by birth injuries like cerebral palsy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and developmental disabilities make sure their families are cared for and have a secure future.

If you are concerned about your child’s developmental delays, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, or developmental delays, we are always available for a free consultation. Our experienced attorneys can help you understand what caused your child’s conditions and help you seek justice for your child.

Featured Videos

Posterior Position

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

Featured Testimonial

What Our

Clients Say…

After the traumatic birth of my son, I was left confused, afraid, and seeking answers. We needed someone we could trust and depend on. ABC Law Centers: Birth Injury Lawyers was just that.

- Michael

Helpful resources

- Spong, Catherine Y., et al. “Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth.” Obstetrics and gynecology 118.2 Pt 1 (2011): 323.

- Graham EM, Ruis KA, Hartman AL, et al. A systematic review of the role of intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia in the causation of neonatal encephalopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199:587.